By Kingsley Williams, CIO & Nico Katzke, Head of Portfolio Solutions

Alexander Pope famously said that “to err is human, to forgive is divine”. When it comes to investing, learning from, and not repeating past mistakes is what we should truly aspire to.

With this in mind, we explore areas in which investors experience biases, and the investment mistakes these sometimes lead to. Indexation strategies can help protect investors from making decisions based on their biases.

Superiority Bias: Being Better than Average

A statement that typifies a superiority bias is: “I am better than average”. While possibly true on the margin, this cannot be true overall.[1] Yet studies have shown that most people (particularly men) rate themselves significantly better than average drivers. We apply a similar rule-of-thumb when it comes to our ability to find better than average managers. But how plausible is this?

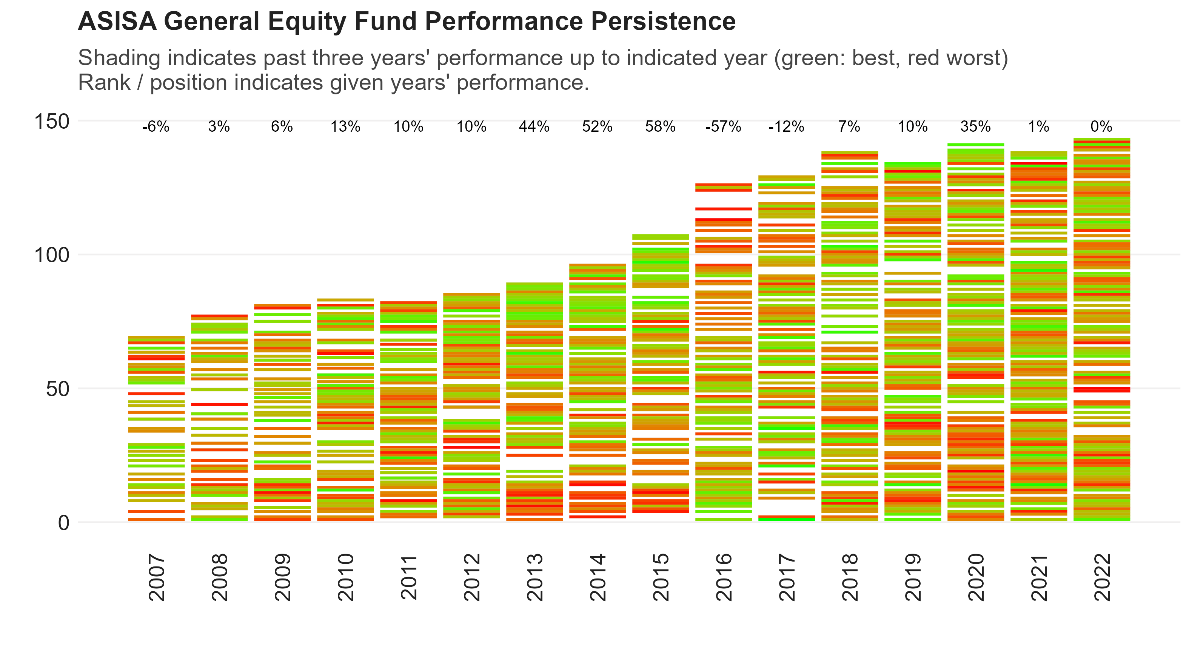

The data to the contrary is clear. Identifying future winners by carefully considering past performance leads to no better result than chance. In the chart below we rank annual active manager performance, while colouring each line according to past 3-year performance (green being a past winner, red a past poor performer). If performance was persistent, we’d see greens mostly at the top and reds mostly at the bottom. The true picture, however, is far more mixed (correlation of past performance above each bar). In fact, since 2015 each year’s past 3-year top quartile performers had worse odds of repeating the feat by luck (23% average).

Source: Satrix & Morningstar retail funds, January 2002 – December 2022

Except in fringe examples where the data is severely skewed, e.g. stating that “I have more fingers than average” would be a correct statement for most (as the average would be just below 10).

Confirmation Bias: Passive Investing is Guaranteed to Underperform.

It is not just that identifying winners is hard. Many investors believe that, even if not a top performing manager, their managers can at least navigate markets successfully and that “passive investing is guaranteed to underperform”. Yet this simply does not hold conceptually or empirically. Nobel Laureate William Sharpe proposed the arithmetic of active management – which suggests active manager performance on average should be in line with a representative benchmark, before fees, and well below after. The data bears this out.

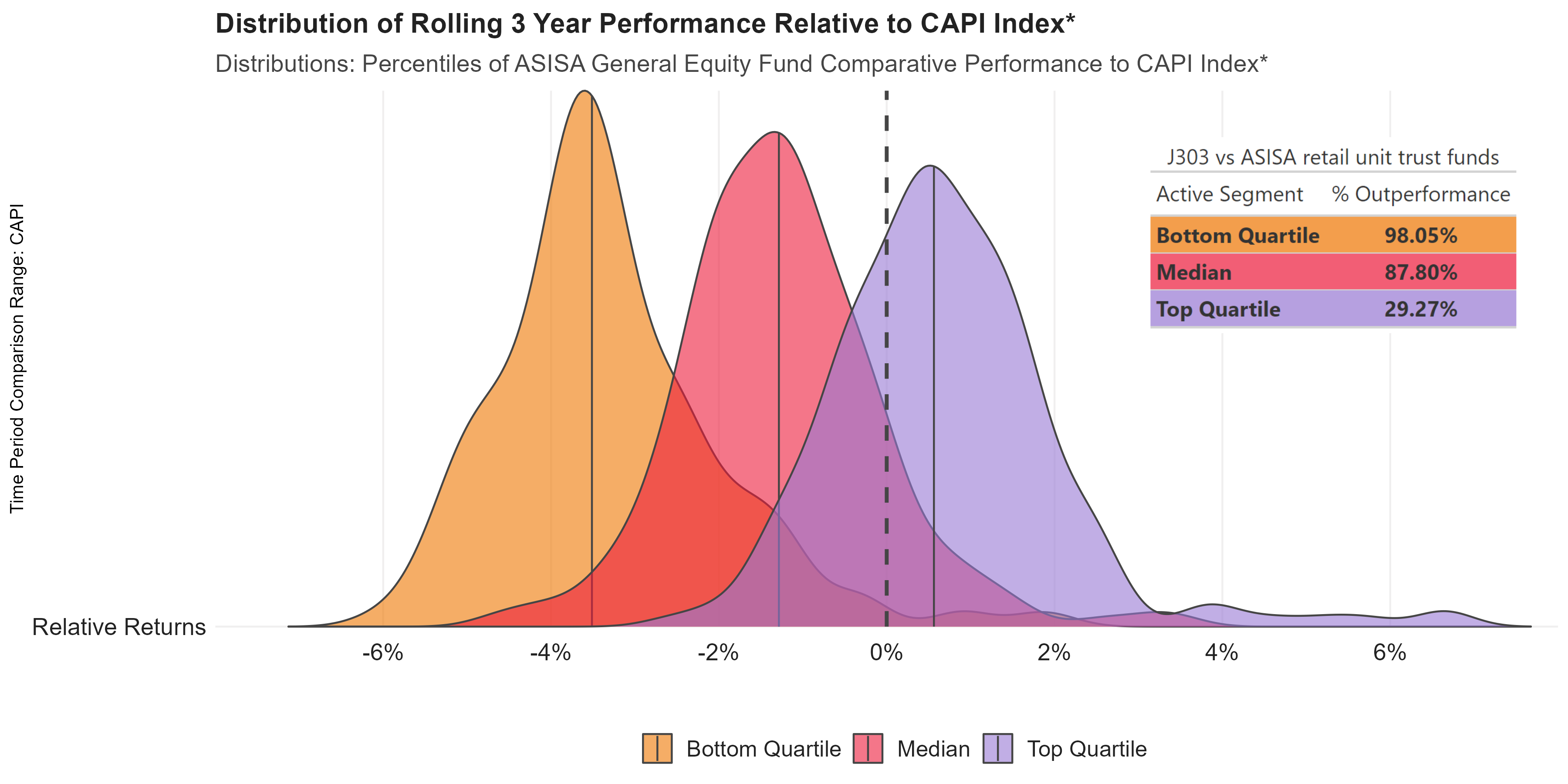

A rolling 3-year comparison of local active manager performance over the past 20 years is shown below compared to the FTSE/JSE Capped All Share Index (after applying a 50bps annual fee). It indicates the median manager underperformed 87% of the time over all 3-year periods, with the index less costs in the top quartile almost a third of the time.

Source: Satrix, Morningstar, FTSE/JSE & Satrix, January 2003 – December 2022. Performance of retail class active funds excluding fund of funds and index funds. | * Benchmark index less 50bps per annum.

This is actually not surprising at all – it follows from significantly lower fees and trading costs on indexed strategies that make outperformance by (mostly) inconsistent managers over the medium term very hard to achieve. These cost benefits put the odds firmly in indexation’s favour - and even marginally favourable odds make repeated plays achieve a near certain outcome (proof of this is the existence of profitable casinos).

Despite the evidence, investors are often confronted with a positive reporting bias – where managers are incentivised to attribute outperformance to skill, and underperformance to temporary factors outside of their control. The highlighting of successful periods while understating poor performing periods further entrenches positive reporting bias. This confirms the bias of indexes not offering attractive performance, and managers’ ability to add value, on average. The data simply does not support this.

Anchoring Bias

Anchoring bias refers to attaching value to arbitrary information. A good example of this (which most investors can relate to) – is evaluating an investment outcome based on the price you paid for it (your anchor price). Selling and realising a loss to this anchored price is painful and thus often avoided – even if evidence suggests holding on might lead to further losses. Realising profits by selling too early is also a typical behavioural trait (an irrational fear of the market somehow realising this and coming to take back its dues). It is often termed “taking profits”, which seems prudent – but makes no sense simply for the sake of doing it. Investment holdings should be unemotionally evaluated based on expectations, not anchored (paid for) prices – which is hard even for seasoned professionals to stick to.

Consistent contributions to index strategies help investors build long-term market exposure, without the distractions of (ultimately irrelevant) short-term price fluctuations. The rules-based discipline also means index managers are not similarly swayed.

Anchoring can also refer to attaching more value to a widely accepted or communicated belief – even if strong evidence to the contrary exists. One such example is the broadly held belief that because markets are complex, investing requires complex navigation to succeed. It needs someone to constantly adjust a portfolio. But this ignores the fact that prevailing market prices are already reflective of all the complexities accounted for by analysts. This makes accurate exploitation of mispricing extremely difficult.

The numbers also suggest this. Various studies have shown long-term strategic asset allocation to be the dominant driver of returns, with tactical (short-term) opportunistic changes seldom adding value.[2] The concept of masterly inactivity applies – where trusting the process pays off long-term.

An indexed approach to managing balanced funds, helps ensure the manager’s focus is firmly placed on that which matters most – long-term allocations. This helps fight the urge to act, incur costs and lock in loss-making decisions. Even if the average manager is right 50% of the time when making tactical decisions, the added trading cost of acting reduces value overall, the impact of which compounds with time.

Consider the performance of the Satrix Balanced Index Fund. This is a long-term oriented indexed approach (rules-based) that applies insight from across the Sanlam group, with modern statistical techniques applied to arrive at an optimal long-term allocation. The process is revisited every second year, with no tactical adjustments made in the interim. This is an exercise in applying masterly activity. Since its 2013 inception, it outperformed industry peers 94% of the time on a rolling 3-year basis (65% rolling 1 year), being in the top quartile more than half the time.

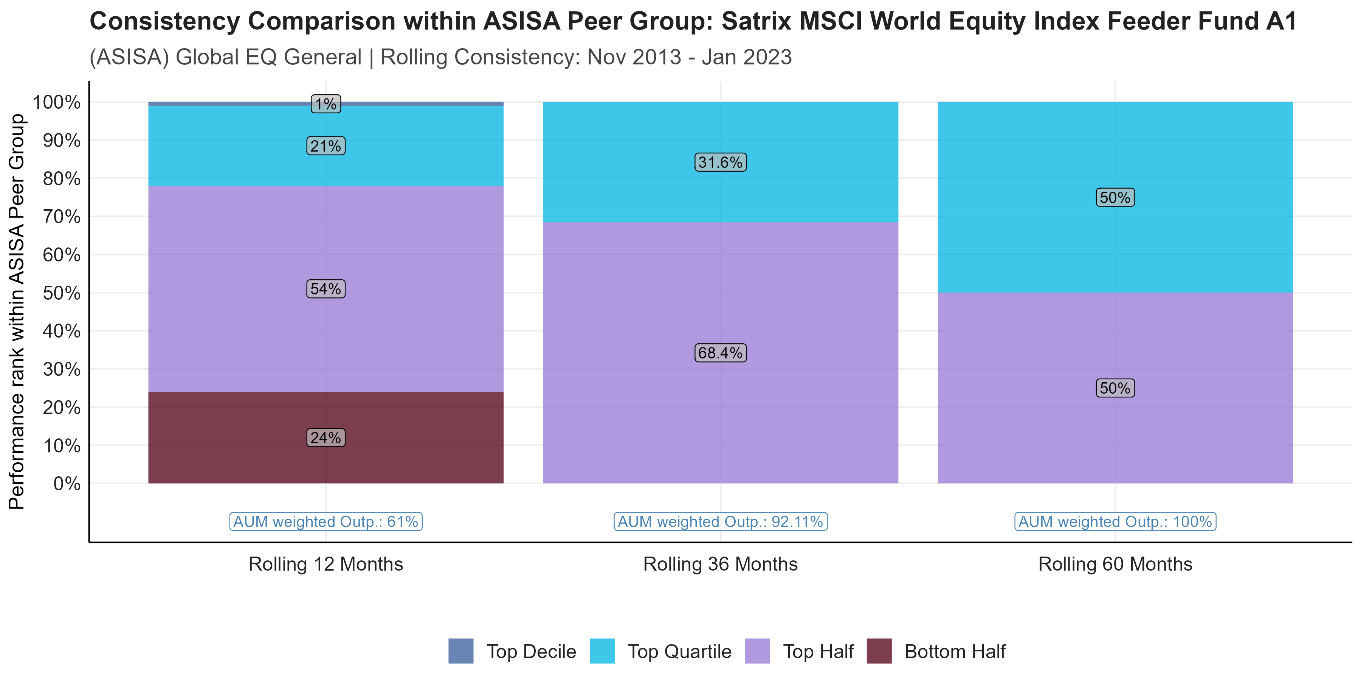

This is not only a local phenomenon. Consider the MSCI World Index. It has, since 2010, always outperformed the median active manager globally[3]. Local managers have also struggled to add value through stock picking in the highly efficient global arena. In fact, since its 2013 inception, the Satrix MSCI World Equity Index Feeder Fund has never underperformed its local active peer group median on a rolling 3-year basis.

See McCarthy & Tower, Static Indexing Beats Tactical Asset Allocation (The Journal of Index Investing, 2021).

Source: Morningstar, calculation: Satrix. We compared the MSCI World Index to a list of between 1500 – 3000 global managers.

Source: Satrix & Morningstar, January 2013 – December 2022

In conclusion, adding value above indexation through consistently accurate tactical allocation is significantly harder to achieve than our anchored beliefs suggest. Remember that the experts we entrust to provide active differentiation are doing so against other experts. All the evidence points to the average investor standing to benefit greatly from indexation. Unless, of course, you are indeed better than the average investor.

Disclosure

Satrix Investments (Pty) Ltd is an approved FSP in term of the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS). The information does not constitute advice as contemplated in FAIS. Use or rely on this information at your own risk. Consult your Financial Adviser before making an investment decision.

While every effort has been made to ensure the reasonableness and accuracy of the information contained in this document (“the information”), the FSP’s, its shareholders, subsidiaries, clients, agents, officers and employees do not make any representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or suitability of the information and shall not be held responsible and disclaims all liability for any loss, liability and damage whatsoever suffered as a result of or which may be attributable, directly or indirectly, to any use of or reliance upon the information.