Quotes are powerful. They can lend credence to arguments and act as persuasive endorsements. But quotes can easily be misconstrued to suit a specific narrative. A perfect example of this is arguably the most famous quote attributed to legendary manager Warren Buffet.

In his 2004 letter to shareholders, Buffet famously states that investors should:

“…be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.”

At the surface he seems to endorse being actively contrarian when investing. Yet the full quote provides a completely different conclusion altogether:

“Over the (last) 35 years, American business has delivered terrific results. It should therefore have been easy for investors to earn juicy returns: All they had to do was piggyback Corporate America in a diversified, low-expense way. An index fund that they never touched would have done the job.

Instead, many investors have had experiences ranging from mediocre to disastrous. There have been three primary causes:

- first, high costs, usually because investors traded excessively or spent far too much on investment management;

- second, portfolio decisions based on tips and fads rather than on thoughtful, quantified evaluation of businesses;

- and third, a start-and-stop approach to the market marked by untimely entries (after an advance has been long underway) and exits (after periods of stagnation or decline).

Investors should remember that excitement and expenses are their enemies. And if they insist on trying to time their participation in equities, they should try to be fearful when others are greedy and greedy only when others are fearful.”

Warren Buffet, 2004 (https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2004ltr.pdf)

What is clear from the full quote above is that Buffet suggests investors would have been well served tracking a simple index strategy and exercising restraint when it comes to changing course. Only at the end does he refer to being actively contrarian, arguing that it makes sense only on that part of their portfolio that investors insist on being active. His recommendation is actually not to be contrarian as a rule, but rather to limit costs, be consistent and reduce timing risks: all enabled through index investing.

This might seem counterintuitive from arguably the best active manager of our time, but considering that he has always been a strong proponent of keeping long-term investing simple and low-cost, not at all out of character. Instead of focusing on the last half of the last sentence, as mostly done, let’s unpack the quote’s three core and overlooked lessons.

1) Avoid High Costs

Compounded returns is a core part of wealth creation – known for working its magic over time to make good strategies great. By the same token, fees and trading costs work to compound against an investment strategy – with the effects being unintuitively severe. As with all things in life, know what you pay and make sure you get a worthwhile bang for buck. Fees should ideally be contextualized to the active risk a strategy takes compared to an investable alternative index, not as a percentage of total assets managed (as is the norm). Sensible investment cost management would be gaining market exposure at an index price level, with true active differentiation being duly rewarded if adding value. Paying more is simply inefficient.

2) Avoid the Urge to Act

A well-diversified approach to investing can be strikingly uneventful and is certainly not known for dramatic highlights. This means we have to consciously accept the virtues of being well diversified as the benefits are not directly observed.

When confronted with stories of concentrated risks paying off (e.g. that one friend who boasts about investing in Sasol at R25 per share, or the colleague who suggested buying a stock that is now up 90% in a quarter), it may seem that investing is simpler than it truly is. Part of the reason is that tales of great success make the lived experience of a diversified approach seem particularly pedestrian. This can make the temptation to chase risky returns unbearable for some. This is further compounded by the fact that the desire to share similar poor investment decisions is not nearly as strong, meaning the cautionary tales of taking concentrated risks is typically sorely missing.

With the benefits of diversification not felt as viscerally as the proceeds of concentrated risks that paid off, investors can be forgiven for not appreciating that even investment professionals, following rigorous and robust processes, prize being diversified and not taking concentrated risks even when having strong conviction. This is a reality of investing that sadly may be widely underappreciated by a large segment of the investment community.

3) Timing Entry and Exit Points Matter Greatly.

Buffet also points to untimely entry and exits hurting investors’ prospects of building long-term wealth. If one considers the non-linear impact of losses versus gains (e.g. losing 60% requires a subsequent gain of 150% to arrive back at parity; compared to a gain of 60% being wiped out by a mere 37% subsequent loss), it is clear that avoiding deep losses is significantly more important than chasing steep gains.

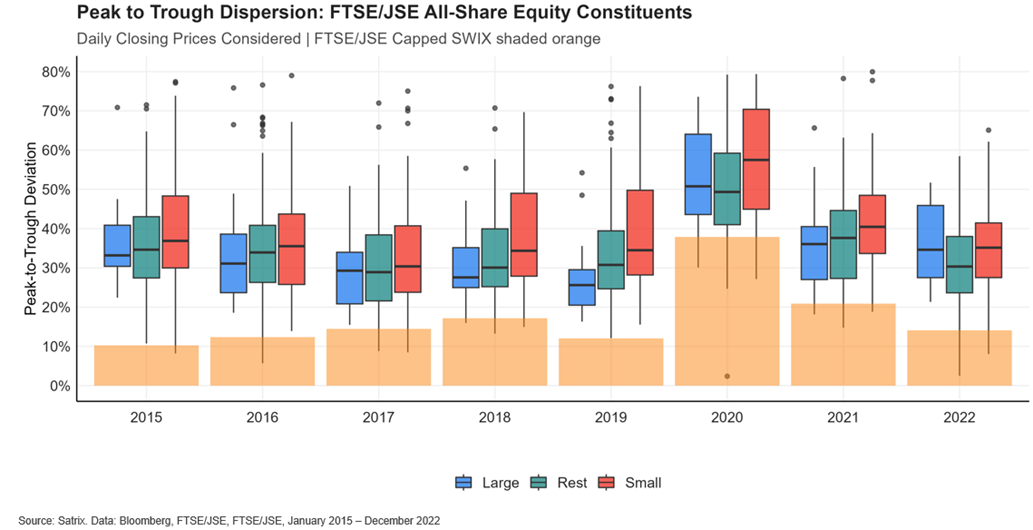

For this reason, investors would do well to reduce the impact of timing their trades – which is likely best achieved by investing in well-diversified investment vehicles. Consider e.g. the differences in peak-to-trough variation when comparing local stocks to a diversified benchmark index like the FTSE/JSE Capped SWIX. The barplots give the top and bottom quartile range for single stock return dispersions in a given year, with the solid horizontal line indicating the median dispersion. The orange shade shows the index dispersion for a given year.

From this graph, note that single stocks deviate on average between 30% – 50% for large-, mid- and small-caps in any given year. This means that timing the purchase of a stock is incredibly important, even if an investor’s long-term view might be correct. Buying at the peak in a given year might very well be followed by significant short-term losses, which, as mentioned, hurt growth prospects far more than being on the right side of a trade. Contrast this to a well-diversified index portfolio that deviates, on average, between 10% and 20% in a given year and it is clear that the timing of building broad market exposure through diversified indexes is far less of a concern.

Conclusion: Swimming with The Tide

In his letter to shareholders in 2004, Warren Buffet clearly advocated for using indexation in an effort to gain market exposure, primarily as it helps investors avoid common investment pitfalls. Being contrarian is argued to be sensible only if one wishes to take an active position.

Buffet’s views on the virtues of low-cost, simple indexation solutions are not predicated on him doubting that there exists opportunities in the active space. On the contrary, active differentiation brought him great success and fortune. Rather, he believes that the biggest impediment to investors not enjoying investment success is that they 1) overpay, 2) overreact and 3) are overzealous in mostly getting their timing wrong.

A simple solution, he stresses, is to use indexation as a dominant part of one’s investment portfolio. The compounded effect of saving in costs (management and trading) and comparatively lower impact of entry and exit points make it a long-term winning strategy.

Being contrarian certainly sounds appealing – if nothing else it is exciting to ‘swim against the tide’ or to ‘not run with the herd’. But there’s a reason fish generally swim with the tide and antelope follow a well-trodden path – it consumes less energy and there’s less likelihood of peril. Similarly, indexes that accept the market’s valuations might not seem attractive at face value, but offer low-cost and diversified exposure to that which truly builds wealth: market exposure. In a world where prices are becoming more efficient and successful active differentiation harder to achieve consistently, this is even more valid than when Buffet made his famous quote.

The lesson Buffet wanted us to learn is that, insofar as being contrarian offers diversification from indexation, it can add value if done well. But at the end of the day, consistency and discipline, not being savvy and smart, is what ultimately brings home the bacon.

Disclosure

Satrix Investments (Pty) Ltd is an approved FSP in term of the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS). The information does not constitute advice as contemplated in FAIS. Use or rely on this information at your own risk. Consult your Financial Adviser before making an investment decision. Satrix Managers is a registered Manager in terms of the Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, 2002.

While every effort has been made to ensure the reasonableness and accuracy of the information contained in this document (“the information”), the FSPs, their shareholders, subsidiaries, clients, agents, officers and employees do not make any representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or suitability of the information and shall not be held responsible and disclaims all liability for any loss, liability and damage whatsoever suffered as a result of or which may be attributable, directly or indirectly, to any use of or reliance upon the information. Full details and basis of the award is available from the Manager.